Teachable Machine Outlier Filter

用户研究

课程名称

05-685 Prototype Algorithmic Experience

帮助Teachable Machine 用户识别和清理训练数据集中的异常值的教学原型设计

合作者

Individual

项目年份

2022

设计挑战

算法偏见通过准确的推荐为用户带来便利, 但也有可能对其有害。 抖音算法系统中的有害偏见如何影响用户体验?

问题陈述-抖音广告推送功能的可用性测试

我们测试了当前抖音功能的可用性,以发现目前存在的算法偏见问题。

1

种族偏见

2

性别偏见

3

品牌偏见

4

需求偏见

5

对偏见广告

消极对待

消极对待

抖音只向资深用户推荐有关用户自己种族的视频,但会向新用户推荐其他种族的视频。

一些受试者删除了其他种族的视频,因为他们觉得这些视频不符合他们的生活方式。

一些受试者删除了其他种族的视频,因为他们觉得这些视频不符合他们的生活方式。

男性受试者收到了有关运动鞋、游戏和性暗示的广告,而女性受试者则收到了有关化妆品和购物的广告。

抖音仅向受试者推荐某些品牌的产品,其中包括电子设备和食品。

受试者不断收到有关他们不想或不需要购买的产品的广告。

尽管受试者对这些商品表示 “不感兴趣”,但抖音仍然向他们推荐这些。

尽管受试者对这些商品表示 “不感兴趣”,但抖音仍然向他们推荐这些。

大多数受试者只在短时间停留在偏见广告上,然后将其划走。

少部分受试者试图对他们看到的前几则偏见广告点击不感兴趣,但很快就放弃了。

少部分受试者试图对他们看到的前几则偏见广告点击不感兴趣,但很快就放弃了。

研究目标

面对潜在的算法偏见,我们如何通过个性化广告设置来赋能用户?

定性分析

我们对3名受试者进行了三轮采访,采用了出声思维法,试点测试访谈,基于引导叙事的半结构化访谈等用户研究方法。

我们记录了这些访谈,并对其使用亲和图和用户旅程图进行分析,以获得更普遍的见解。以下是我们最关注的几个问题:

我们记录了这些访谈,并对其使用亲和图和用户旅程图进行分析,以获得更普遍的见解。以下是我们最关注的几个问题:

“你对抖音上存在偏见的广告有何看法?”

“你对当前的广告设置用户流程有何看法?正面和负面观点多多益善。”

“你希望抖音将来添加更多广告功能吗?为什么?你认为这如何有助于应对算法偏见并使算法满足你的需求?”

“你对刚才提到的潜在功能有疑虑吗?”

“你希望我们对广告设置界面/用户流程进行哪些改进?”

数据分析整合 - 笔记解读 + 亲和图

通过对采访笔记的解读,我们分析用户的需求、动机和行为,然后将他们分组并标记成亲和图,以第一人称视角整合见解。用户阐明了他们在抖音上的偏好、活动和发现,分享了他们的需求、建议、疑虑和关注点。

模型-用户旅程图

我们构建了模型 - 用户旅程图,以更好地帮助我们总结和理解用户的立场,为速配设计提供了设计启示。

定量分析

我们还进行了问卷调查,包括3 个类别的 13 个问题: 应用功能、广告和购买行为。调查结果验证了我们从定性研究中得出的初步结论。我们总计收到了 32 份回复, 这些结果帮助我们迭代了结论以及接下来的快速约会。

大多数受试者介于22-25岁之间,使用抖音每天不到一小时。

该调查证实了我们在访谈中得出的关于当前广告设置的问题,以及人们对广告设置教程的强烈需求。广告设置应更容易找到,以及互动提示在受访者中很受欢迎。

该调查证实了人们尽管有时从未意识到,但在抖音上还是会遇到偏见广告,包括 从广告中购买产品 (有益偏见)和 接收不当或虚假的广告 (有害偏见)。

该调查揭示了受访者的对推荐广告的兴趣。

设计启示

1

有益与有害的

算法偏见

算法偏见

2

渴望消解偏见

3

多样的广告

偏好设置

偏好设置

4

改善指引界面

5

无缝功能集成

用户喜欢带有有益偏见的广告,但也承认算法偏见带来的相关问题,尽管有时他们没有意识到。

对感兴趣的类别进行个性化设置反映了用户希望通过控制他们遇到的广告类型来消解算法偏见。

用户对不同的广告偏好设置机制表达了兴趣,但更喜欢简单直观的机制。

广告相关操作和设置隐藏太深,为用户带来了繁琐的个性化体验,因此需要改进

用户表达了使用抖音时的无缝体验需求,这需要整合个性化功能和现有功能。

低保真原型

速配设计

我们以设计启示为基础,使用速配设计来帮助我们探索可能的设计方向,验证用户需求并确定风险因素。

大多数受试者对方案一表达认可。

大多数受试者对方案一表达认可。

-大多数参与者对实时反馈感兴趣。

-用户更喜欢简单直观的功能。

-用户更喜欢在抖音“为你推荐”页面上进行简单的互动。

-用户更喜欢简单直观的功能。

-用户更喜欢在抖音“为你推荐”页面上进行简单的互动。

-我们希望添加插件以消除广告偏见,但大多数人认为它过于复杂。

-尽管分享偏好的想法比较新颖,但大多数受试者表示困惑。 这引发了他们对隐私和日常社交互动模式的不安。

低保真原型

以最初的速配设计为基础,我们使用低保真原型进行了情景原型测试,我们共招募了7 名受试者。在测试过程中,我们确定了用户体验中的三个关键时刻:打开抖音、连续划走, 他们多次观看完整广告。为了进一步探索这些时刻,我们将交互提示做成了纸质原型并在现实生活中的环境进行了测试 - 要求受试者在自己的手机上使用抖音。

成果评估

原型测试的总体反馈是积极的,我们的设计方案极大地提高了用户的满意度。但是纸质原型的设计存在缺陷,影响了测试流程的连续性。考虑到最终的设计呈现方式,积极的反馈更多地影响了我们的最终决定。

最终设计原型

我们在此介绍针对算法偏见的广告个性化插件的设计方案。由于我们的方案以插件的形式呈现,因此我们利用当前抖音UI设计的组件与设计风格,并将我们的插件集成到当前的用户使用流程中。

场景 1:使用教程

我们将隐藏起来的 “不感兴趣” 按钮移到了右列 “喜爱” 按钮附近。当用户首次打开抖音时,插件将展示此功能的使用教程。

场景 2:交互提示

当用户持续上划跳过视频时,将出现交互提示。根据不同选项,插件做出不同响应:调整推荐(显示更少或更多的相似内容)或导航到举报页面。

场景 3:个性化设置提示

如果用户多次观看完整广告,插件将提示他们选择自己的偏好并引导他们进入广告个性化页面。在这里,用户可以通过选择个性化标签自定义偏好,以便于更好地控制收到的广告。

问题陈述

异常值出现场景

TM的设计缺陷

潜在的设计方向

大型数据集可能发生异常值:很难检测,但可能会对预测结果产生巨大影响。

数据采集过程中的网络摄像头误入者:连续捕获的机制使清楚过程变得困难。

人为引入的多样性:人类无法精确控制异常值的影响,这可能会阻碍预测的准确性。

Teacable Machine 将所有输入值作为训练数据,但无法识别数据集中的异常值。

预测机制隐藏得太深,对不了解机器学习技术的用户不友好

我们可以通过引入人为本的方法帮助用户识别异常值

简单的预测机制和适当的可解释性可以帮助用户发现潜在异常值的影响。

研究目标

我们如何提供反馈,让用户了解异常值对训练集准确性的影响,从而提供更高质量的训练数据样本?

-(RQ1): 界面如何提醒人们可能不小心将异常值引入了训练数据集?

-(RQ2): 界面如何指导用户利用TeacableMachine提供的原理阐释有效过滤异常值?

-(RQ2): 界面如何指导用户利用TeacableMachine提供的原理阐释有效过滤异常值?

原型设计

初始解决方案 01:人工监督分类

初始解决方案 02:被动异常值识别和校正

最终解决方案:“警报” 界面和 “异常值过滤器” 界面。

原型测试

我在 5 名参与者身上测试了原型。1 名参与者拥有计算机科学背景,2 名拥有设计背景(建筑),2名来自跨学科背景(人机交互和认知科学/管理)。他们中的大多数人具有机器学习或统计学的基础知识。

第 1 回合:教程(对照组)

第 2 回合:使用经过人工筛选的训练集训练新模型

第 3 回合:使用新训练集应用新模型

让受试者运行 TM 并观察当前数据集在对指定样本分类的工作原理。

在接下来的回合中,从两个警报界面备选方案中选择最喜欢的,作为异常值过滤器界面的测试原型。

让受试者通过删除清单中建议的异常值手动优化训练集。

再次在新数据集上运行 TM,观察准确度如何变化,同时试图学习异常值范式。

让参与者根据从第 2 轮中学到的异常值范式手动筛选新的数据集,再次运行 TM 并观察预测准确度如何变化。

进行半结构化访谈和问卷调研

“警报”界面的纸质原型

异常值清单

(红色标注:建议异常值,删除标注:受试者选择的异常值)

(红色标注:建议异常值,删除标注:受试者选择的异常值)

定量分析

下图展示了5名受试者在3轮测试中对样本的预测精度。已过滤的数据集准确度最高。但是与初始回合相比,由于受试者可能从建议中学习了异常值的范式,手动筛选的精度显著提高。

定性分析

我通过调研问卷和半结构化访谈获得了更多的信息,参与者表达了他们在这个过程中的发现、感受和建议,为后续总结设计启示提供了宝贵的观点。

关于界面设计

对于“警报”界面,受试者首选第二个设计:

- 他们可以从中看到预测准确性,并理解删除异常值的意图。

- 它鼓励他们考虑进一步优化方式以获得更好的性能。

对于“异常值过滤器"界面,参与者将更好预测结果归因于简单明了的设计。

- 他们可以从中看到预测准确性,并理解删除异常值的意图。

- 它鼓励他们考虑进一步优化方式以获得更好的性能。

对于“异常值过滤器"界面,参与者将更好预测结果归因于简单明了的设计。

其他发现

受试者对TeacableMachine的算法机制表示的好奇心超出了预期。尽管他们愿意进一步了解该算法,但他们在测试过程中尽量与算法保持距离,具有专业背景的受试者对第二轮的判断充满信心,但第三轮的结果让他们感到失望。

设计启示

“警报” 界面激发了人们了解影响预测表现的因素的欲望。

“异常值过滤器” 界面为用户提供了一种让他们了解如何区分异常值以及它们对模型的影响的设计范例。

“异常值过滤器” 界面为用户提供了一种让他们了解如何区分异常值以及它们对模型的影响的设计范例。

迭代建议

更多研究问题

受试者的反馈,尤其是他们的困惑,带来了进一步推测的潜力,其中包括:

- 为什么谷歌将原理阐释放在了高级功能中?

- 如何平衡人为引入的偏见和机器学习模型偏差?

- 过滤系统在不可预测的新数据集上的表现如何?

- 为什么谷歌将原理阐释放在了高级功能中?

- 如何平衡人为引入的偏见和机器学习模型偏差?

- 过滤系统在不可预测的新数据集上的表现如何?

界面迭代建议

他们还就进一步的界面迭代提供了宝贵的建议,其中包括:

如何查看数据集:

-行布局(集成到TM当前的上传界面)

-页面预览(集成在上传界面后)

如何识别标记的异常值:

-现场标记

-针对所有分类组的异常值分区

-针对每个分类组的异常值分区

如何回溯筛选流程:

-存档分区(备份性能最佳的筛选数据集)

-行布局(集成到TM当前的上传界面)

-页面预览(集成在上传界面后)

如何识别标记的异常值:

-现场标记

-针对所有分类组的异常值分区

-针对每个分类组的异常值分区

如何回溯筛选流程:

-存档分区(备份性能最佳的筛选数据集)

这个项目

Piggyback 原型设计,用于测试社交平台连接中社交机器人的有效性/可爱度

研究目标

社交机器人通过在Twitter上直接发送经过处理的信息来鼓励私人一对一的联系有多有效(有效性),以及人们对这种连接方式(可爱度)的看法(可爱度)如何。

问:什么是一对一连接?

答:促进与陌生人的联系(关注)和关注者之间的联系(聊天)的能力

答:促进与陌生人的联系(关注)和关注者之间的联系(聊天)的能力

战略

推荐类似的 朋友/话题 基于 相似性 最近喜欢考试的推文有:

-后续机器人消息如何有效地连接用户?

-参与者对这种方法的态度如何影响他们的行为?

-参与者对这种方法的态度如何影响他们的行为?

原型设计会议

我根据参与者在Twitter上的地理位置来选择参与者。他们中的大多数人住在匹兹堡。

推荐系统:从推特上抓取

作为推荐机器人的一部分,我编写了一个 python 抓取脚本来计算两个用户之间的相似度。为了找到潜在的推荐用户,我提取了那些喜欢与参与者相同推文的用户,并分析了他们最近点赞的推文的相似之处。如果他们的相似度超过设定的阈值(85%),我将对话中与特定主题相关的前三个主题标签作为连接内容。

推荐系统:对话树

我建立了一个对话树,根据当前原型设计会话的目的和层级响应来组织如何向参与者发送提示。

推荐系统:人类机器人

完成上述准备工作后,我创建了一个 “官方” Twitter账户,并开始根据回复手动发送后续提示(当时没有自动化技能哈哈)。如果参与者愿意协助该项目,它将收到一份问卷。

原型制作会议:搭便车原型设计和角色访谈

原型设计课程由两部分组成,每个部分有50名参与者。Piggyback II 不包括关注参与者的用户。因为结果没有得到足够的反馈进行分析,所以我进行了角色访谈

定量分析

从关注提示的用户百分比来看,效果并不乐观。我对100名随机参与者进行了测试,但该原型设计的临界质量尚不清楚。

在不增加被屏蔽率(降低可爱度)的同时,后续问题会引导参与者隐含地检查和遵循指令。

在不增加被屏蔽率(降低可爱度)的同时,后续问题会引导参与者隐含地检查和遵循指令。

定性分析

在采访中,参与者认为以下因素会影响参与者对机器人的回应意愿:

-隐私问题:如果机器人获得认证,将影响用户对其消息的信任。许多潜在的参与者选择对陌生人关闭DM入口,或者在个人资料中不包含DM消息。

-类人关卡:类人形象/反应将获得更多用户的同情。

-算法透明度:不透明的算法会使那些无处收到消息的人感到恐惧。

-隐私问题:如果机器人获得认证,将影响用户对其消息的信任。许多潜在的参与者选择对陌生人关闭DM入口,或者在个人资料中不包含DM消息。

-类人关卡:类人形象/反应将获得更多用户的同情。

-算法透明度:不透明的算法会使那些无处收到消息的人感到恐惧。

见解与启示

直接消息是发送机器人消息的一种烦人的方式,可以解释为什么只有某些人会回复机器人。

该原型设计的临界质量尚不清楚,可能需要超过100个样本才能收集足够的反馈进行分析。

后续问题积极提高了参与者的注意力和好奇心。但是,从关注提示的用户百分比来看,效果并不乐观。

该原型设计的临界质量尚不清楚,可能需要超过100个样本才能收集足够的反馈进行分析。

后续问题积极提高了参与者的注意力和好奇心。但是,从关注提示的用户百分比来看,效果并不乐观。

下一步

这个原型设计练习几乎不是一次成功的尝试,但它让我对下一步有了很多见解:

连接机器人设计:

-有了更好的编程技能,我可以考虑将整个过程自动化,以获得更大的搭载尺寸。

-没有任何机制鼓励参与者就对话提供反馈(他们是否想接收消息以及他们对此的感受)。同时,对话树还应鼓励参与者隐含地回应机器人提示。

原型制作算法:

-相似度还可能包括个人资料/主题标签/新推文/回复,更合成的算法可能会提高推荐准确性并带来更多积极的反馈。

-有了更好的编程技能,我可以考虑将整个过程自动化,以获得更大的搭载尺寸。

-没有任何机制鼓励参与者就对话提供反馈(他们是否想接收消息以及他们对此的感受)。同时,对话树还应鼓励参与者隐含地回应机器人提示。

原型制作算法:

-相似度还可能包括个人资料/主题标签/新推文/回复,更合成的算法可能会提高推荐准确性并带来更多积极的反馈。

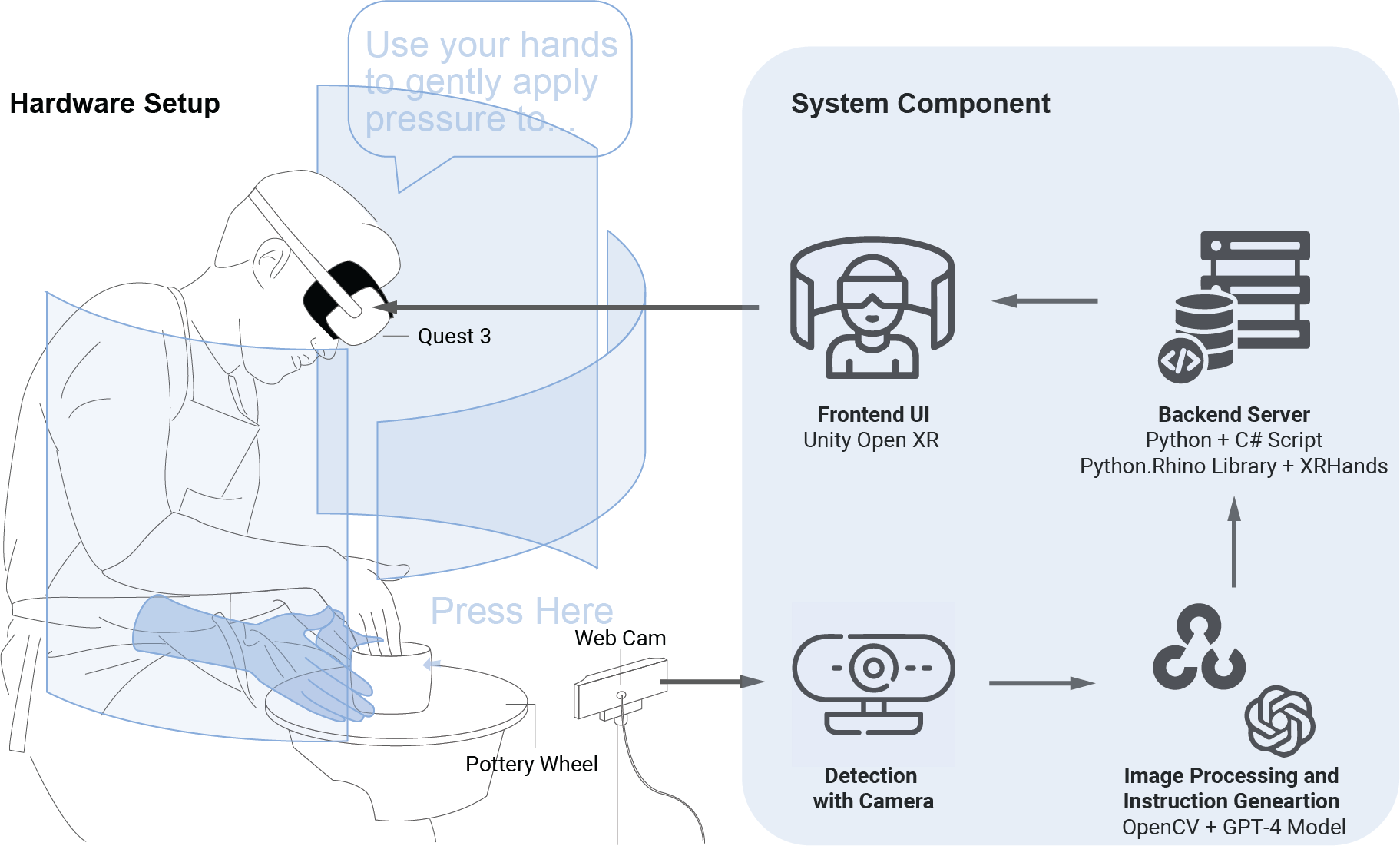

陶艺教学系统概览

该系统的功能源于设计目标,具体功能则参考了民族志研究的结果。 在本节中,我们将介绍系统设置,并对其功能进行详细说明,同时简要介绍其技术实现情况。

系统设置

我们使用 VEVOR 9.8" LCD 触摸屏拉胚机 GCJX-008 作为主要设备,并使用Logitech C920 摄像头捕捉陶土形状数据。为确保陶土与背景之间的清晰区分,我们使用黑布包裹墙角并移除了泥水托盘。 我们的系统基于 Meta Quest3,利用其透视功能让用户与周围环境进行互动。设置过程非常简单:用户戴上头显,坐在拉胚机前,选择适当的速度和模式,并使用手柄初始化所选教程,然后练习手工制作陶器,同时使用语音指令来控制系统引导。

功能详解

我们在系统中提出了两个核心功能,并根据形成性研究中确定的学习者的两个技能水平的各自需求对其进行了定制和重组。

核心功能

我们在系统中确定了两个核心功能: 1. 手势与目标形状全息投影作为沉浸式教程;2. 基于空间形状的纠正、指导和建议作为反馈。

手势与目标形状全息投影

系统提供手势与目标形状全息投影,从第一视角显示每个步骤的手势和目标形状。 手势全息投影根据民族志研究总结的步骤示意图创建,在 Blender 中建模,导出为 .fbx 动画,并作为预制件导入 Unity。 在手势识别方面,我们使用 XRHand 插件将手势识别可视化为基于文本的指令,并简化了语言,使其更易于理解,确保不同技能水平的学习者都能使用。

基于空间形状的反馈

我们的系统提供三种类型的反馈:纠正、指导和基于目前陶土形状的建议。 我们使用OpenCV 捕捉陶土形状轮廓,并使用 Rhino.Python 库识别关键位置。 然后,将当前形状与目标形状进行比较,生成相似度评分和布尔值,从而评估目前进度。 评估结果将通过两种方式进一步处理: (1) 根据已识别的关键位置位置的比较结果,使用 OpenAI API 生成基于不同技能水平的个性化提示。 (2) 在目标形状/当前形状轮廓的交叉点上创建多个轮廓切片,然后对其进行扫描以创建空间形状投影。 这两种数据都通过服务器发送到系统中并可视化: (1) 在锚点上生成三种颜色的全息投影:红色代表 "向内推",绿色代表 "形状正确",蓝色代表 "向外拉"。 (2) 多模态教程指令。

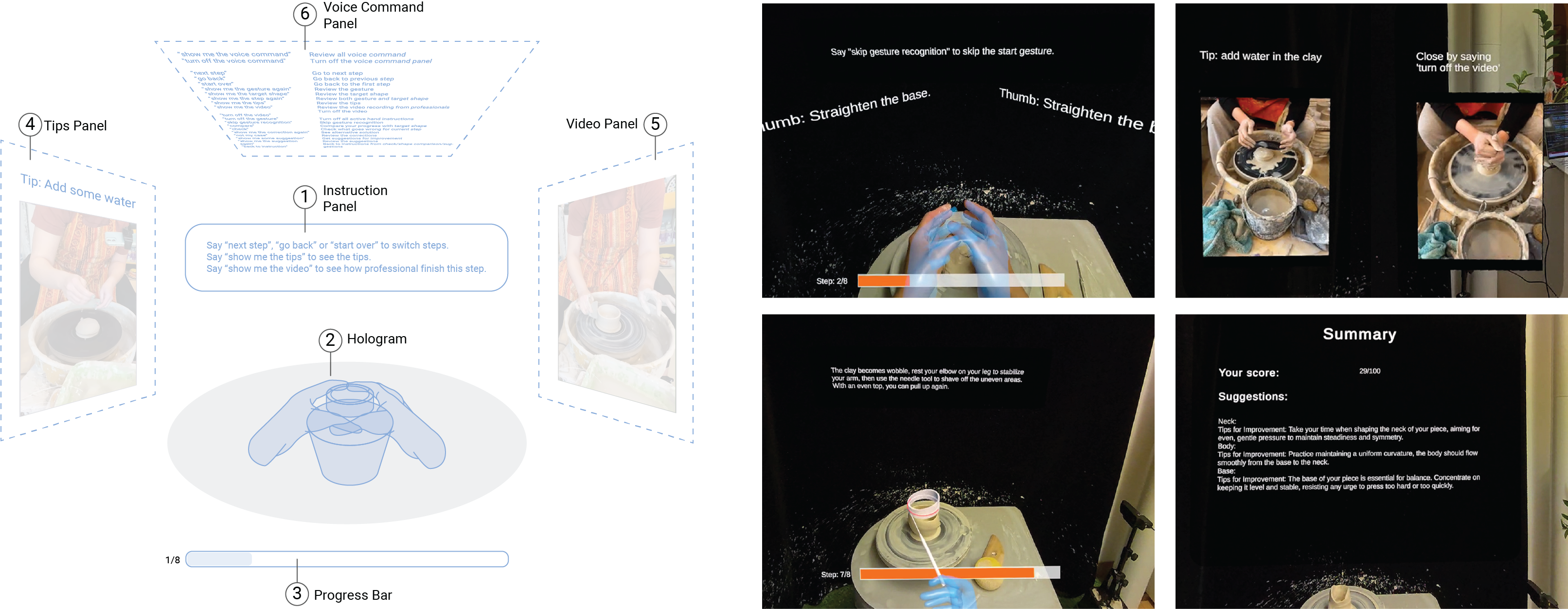

新手教程: 逐步学习

新手通常对陶瓷制作的熟练程度有限。 他们不太熟悉每个步骤,缺乏拉胚技术的练习,因此需要基本的反馈来改进自己的练习。 该系统可在学习过程中和学习结束后提供详细的分步教程和易于理解的反馈。

学习流程:观看、模仿和实践

从民族志研究中,我们观察到学生们会观察并跟随指导教师的动作,老师们也会偶尔纠正学生们的手势。 由于陶瓷制作要求高精度,正确和精确的手势在拉胚中至关重要。 然而,传统的教学方法往往难以在过程中提供手势的实时反馈。 我们的系统采用了类似的流程,但增强了体验:学习者首先观看全息动画来观察手势,然后根据实时手部建议模仿起始手势,并练习从全息投影中学到的动作。

空间学习: 全息投影、视频教学和提示

拉胚要求学习者在空间中塑造陶土。 根据我们的观察,在传统的工作室环境中,仅靠观察往往不足以捕捉手部动作的微妙细节及其与粘土的互动;即使有手把手的指导,学习者的观察通常也仅限于第三人称视角。 我们的系统利用混合现实技术,提供:1)第一人称叠加全息投影展示手与粘土之间的关系,让用户仔细观察并理解手势的复杂细节;2)第三人称演示视频和专家提示,通过传达湿润度、压力和速度等因素,还原传统工作室的知识传递。 该系统增强了学习者对陶器制作的显性和隐性方面的理解,弥合了传统和沉浸式学习体验之间的差距。

从反馈中学习

对于新手来说,在学习过程中遇到困难时获得反馈并学会如何在下一次尝试中改进是至关重要的。 我们的系统可以在 "关键事件 "中提供纠正,还原现场学习体验。 系统还能生成时候事后总结,对最终的陶器形状提出建议,让学习者能够反思当前结果,并在下一回合中提升技术。

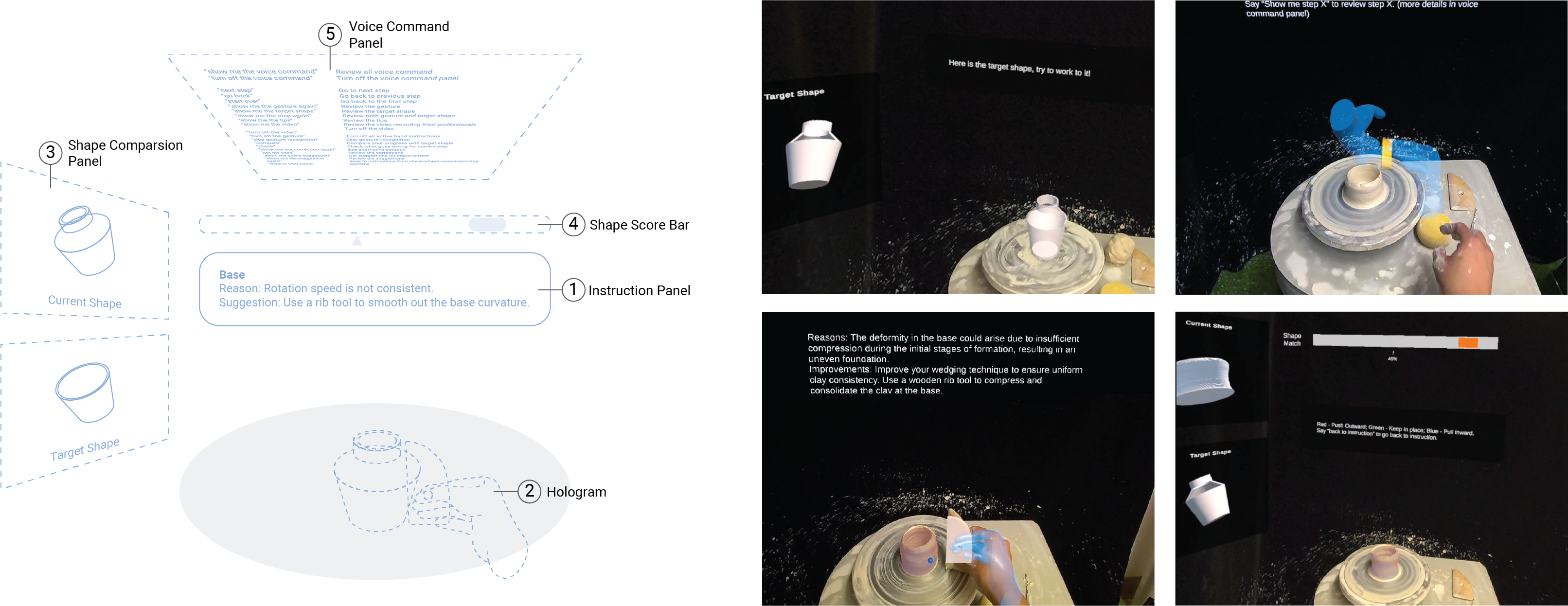

进阶使用: 引导与学习

有经验的学习者已经掌握了制作陶瓷的必要技能,但仍有改进的空间。 该系统旨在为他们提供独立操作的自由,同时为他们完善作品提供支持,通过强化实践提高他们对拉胚工艺的理解。

技术重温与参考

在我们的陶瓷学习和先导实验中,我们观察到有经验的学习者有时需要重温技能。 他们可以随时回顾手势和形状全息投影来强化自己的技术。 系统还可在侧面实时显示当前和目标形状以供参考,因此他们可以灵活地按照自己的节奏制作陶器,同时根据需要定期参考。

形状引导

对于有经验的学习者来说,目标已从简单地塑造一个像样的陶陶器转变为追求完美。 我们提供实时彩色叠加全息投影,在制作过程中通过比较当前形状和目标形状来指导他们塑造陶土。 他们可以参考投影并相应地修正形状。

多模态指导

对于有经验的学习者来说,他们对技巧和工具的深入了解使他们对指导有了更高的期望。 在新手模式事后总结的基础上,我们的系统根据陶器的基本组成部分提供多模态指导,将文字、音频和手势/形状全息投影整合在一起。 这种多模态方法提供了更详细的信息,使有经验的学习者更容易吸收和扩展他们的知识。

视频演示

研究背景

该研究探讨了大语言模型(LLM)幻觉与具身媒介(embodied medium)的纠缠。幻觉作为一个新兴的概念,其以设计为导向的视角 尚待探索。当前的算法体验(AX)原型设计方法提及了算法的负面影响,但没有详细说明如何处理 这些“错误或不可预测” 的结果,它也只探讨了虚拟和有形的算法体验,并从以人为本的设计角度进行探索。因此,本研究提出通过将算法体验扩展到更广泛的具身媒介来设计幻觉体验,并将算法体验原型制作方法用于思辨设计。 为了更好地传达体验,本研究侧重于两种相遇情景:从第一人称角度研究多模态作为体验传达媒介的潜力,并从第三人称角度将思辨设计与实体材料之外的更广泛的具身媒介相结合。

当前研究的空白与机遇

叙事媒介 -

第一人称和第三人称

第一人称和第三人称

研究问题

当大语言模型幻觉融入日常的具身互动体验时:

(RQ1)-用户如何识别、解读幻觉并与之产生共鸣?

(RQ2)-设计师如何通过来自用户的启示,通过具身媒介和理论来设计幻觉体验?

(RQ1)-用户如何识别、解读幻觉并与之产生共鸣?

(RQ2)-设计师如何通过来自用户的启示,通过具身媒介和理论来设计幻觉体验?

研究假设

交互过程中的算法经验

算法逻辑/机制体验: 这种体验源于算法的工作原理。对于机器学习中基于预测的算法,输入输出关系清晰可见。相比之下,大语言模型通过预测的代币序列生成结果,由于输出基于自然语言,用户对其的影响更间接,从而导致了不同的交互体验。

来自算法生成内容体验: 这种体验侧重于算法生成内容类型。对于大语言模型而言,生成的文本、语音、图像或3D 模型均提供不同的体验,具体取决于特定情景中的模态。

来自人为解读的体验: 用户根据自己的社会技术背景来解释算法输出,从而根据他们与结果的互动方式产生不同的反应和体验。

来自算法生成内容体验: 这种体验侧重于算法生成内容类型。对于大语言模型而言,生成的文本、语音、图像或3D 模型均提供不同的体验,具体取决于特定情景中的模态。

来自人为解读的体验: 用户根据自己的社会技术背景来解释算法输出,从而根据他们与结果的互动方式产生不同的反应和体验。

幻觉体验词汇表

这里的幻觉综合了导致了回复偏差各种技术问题。这些问题起因不同,产生的结果也不同,并且在很大程度上受社会技术背景的影响。我提出以下词汇表作为想象潜在幻觉体验的切入点:

同理心 — 来自技术缺陷的情感体验: 这种视角源于用户对幻觉的解读。有些人表示沮丧,而另一些人则将幻觉视为陪伴,在错误但温和的反馈中寻求情感支持。技术缺陷变成了一种个人的情感体验。

机缘巧合 — 与社交关系产生共鸣的另类体验: 这种体验来自幻觉所导致的意料之外的社会关系,以激发好奇心、同理心和反思。这些偶然的时刻可以帮助用户以有意义的方式与更广泛的社交情景建立联系。

炼金术 — 来自幻觉内容的创造性体验: 在内容生成中,幻觉虽然会生成不准确的结果,但可以激发创造力。用户可能会产生超出他们认知或期望的灵感,将幻觉转化为创造性探索的催化剂。

同理心 — 来自技术缺陷的情感体验: 这种视角源于用户对幻觉的解读。有些人表示沮丧,而另一些人则将幻觉视为陪伴,在错误但温和的反馈中寻求情感支持。技术缺陷变成了一种个人的情感体验。

机缘巧合 — 与社交关系产生共鸣的另类体验: 这种体验来自幻觉所导致的意料之外的社会关系,以激发好奇心、同理心和反思。这些偶然的时刻可以帮助用户以有意义的方式与更广泛的社交情景建立联系。

炼金术 — 来自幻觉内容的创造性体验: 在内容生成中,幻觉虽然会生成不准确的结果,但可以激发创造力。用户可能会产生超出他们认知或期望的灵感,将幻觉转化为创造性探索的催化剂。

研究方法

原型制作幻觉体验

原型 01:Moodie Assistant

关键词:同理心,情感投射,解释的模糊性

Moodie Assistant 将算法体验描述为对幻觉的情感反应。该原型采用实体语音助手的形式,但设计了指示幻觉程度的表盘。它还配备了一系列遥控器,使用户/观众可以在对话中以不同的互动方式和精度投射自己的情感体验。不同的角色、用户和受众,在与设备互动时会有不同的情绪反应。原型为我们提供了讨论解释模糊性的媒介。

关键词:同理心,情感投射,解释的模糊性

Moodie Assistant 将算法体验描述为对幻觉的情感反应。该原型采用实体语音助手的形式,但设计了指示幻觉程度的表盘。它还配备了一系列遥控器,使用户/观众可以在对话中以不同的互动方式和精度投射自己的情感体验。不同的角色、用户和受众,在与设备互动时会有不同的情绪反应。原型为我们提供了讨论解释模糊性的媒介。

原型 02:Whisper Web

关键词:机缘巧合,社交偶遇

WhisperWeb 将幻觉体验视为社交偶遇。该原型以聊天助手的形式呈现,通过收集使用者的对话作为上下文 ,用于模拟语言模型的 “训练集”。该原型试图反思当幻觉导致的错误情景反而暗示了不同的社会情景时人们的反应。该原型没有对用户的交互进行直接干预,而是利用可视化媒介来观察和记录幻觉如何导致人与对话代理媒介之间的关系变迁。

关键词:机缘巧合,社交偶遇

WhisperWeb 将幻觉体验视为社交偶遇。该原型以聊天助手的形式呈现,通过收集使用者的对话作为上下文 ,用于模拟语言模型的 “训练集”。该原型试图反思当幻觉导致的错误情景反而暗示了不同的社会情景时人们的反应。该原型没有对用户的交互进行直接干预,而是利用可视化媒介来观察和记录幻觉如何导致人与对话代理媒介之间的关系变迁。

原型 03:Mindscape

关键词:炼金术,幻觉转化为创意

Mindscape通过从幻觉中寻求创造性机会来构建体验。该原型是沉浸式平台上的扩展现实应用程序,允许用户使用强化了幻觉的语言模型构思和创建另一个虚拟世界,该模型更多地关注头脑风暴的工作流程:构思与迭代。该原型旨在研究幻觉影响下的生成内容对创造力的影响。该原型摆脱了现实物理世界的限制,最大限度地解放了想象力。

关键词:炼金术,幻觉转化为创意

Mindscape通过从幻觉中寻求创造性机会来构建体验。该原型是沉浸式平台上的扩展现实应用程序,允许用户使用强化了幻觉的语言模型构思和创建另一个虚拟世界,该模型更多地关注头脑风暴的工作流程:构思与迭代。该原型旨在研究幻觉影响下的生成内容对创造力的影响。该原型摆脱了现实物理世界的限制,最大限度地解放了想象力。

思辨电影 — 体验叙事

(试点)用户研究

通过口耳相传的方法,研究招募了六名受试者,所有受试者都是项目的其他学生或毕业生。所有受试者都有丰富的设计实践经验,熟悉与大语言模型相关的应用程序/工具。他们被分成三组,连续三天进行了三次观察研究。在观察研究和随后的访谈中,研究人员可倾听受试者“说” 的内容,并观察他们 “做了什么”。在使用亲和图和交互式可视化分析收集到的数据后,研究者在接下来的一周举办了一次工作坊,进行研究反思和探索性参与式设计,邀请受试者作为设计专家与用户提出 “解决方案”。

发现

(红色:识别;黄色:解读;蓝色:共鸣)

识别

解读

共鸣

1

大语言模型幻觉特征

自然语言伪装下的虚假回复

对模型能力有限的同情

对人类的期望是否与模型解释保持一致的疑虑

模糊的解读引发的复杂情感反应

混淆微妙的事实扭曲

2

具身媒介对幻觉体验的影响

媒介对幻觉的可解释性

幻觉的来源

与媒体互动产生的同理心

媒介对幻觉的指示能力

模态的可解释性

幻觉与媒介特性的适配度

媒介的学习负担

幻觉和原型技术之间的相互作用

3

幻觉体验中的互动模式

来自无关的回复内容

由无关的或难懂的回复触发

当幻觉与用户的意图、情感和社交距离保持一致时(内在准则)

来自异常的回复模式

由对错误上下文的意外共鸣触发

在尊重算法错误和幻觉之间的界限时(价值判断)

设计启示

1

在幻觉识别

和共鸣的界限

进行原型设计

和共鸣的界限

进行原型设计

2

基于幻觉和媒介

的本质进行

原型设计

的本质进行

原型设计

3

为关键的、有影响力的时刻

进行原型设计

进行原型设计

4

以最小的学习负担

进行原型设计

进行原型设计

设计师在设计幻觉体验时,需要在清晰识别算法错误和幻觉之间取得平衡,以唤起用户的同理心,与体验建立更深层次的联系。这种平衡可确保用户能够与幻觉产生共鸣而不会被明显的错误分散注意力。

幻觉是否更适合以事实知识或抽象概念进行表达,选取的具身媒介是否增强了其可解释性和用户参与度?原型设计应符合这些特征,不仅可以为未来的设计提供见解,还可以更有效地与受众进行沟通。

虽然一些幻觉时刻,例如事实错误或脱离上下文的回应,是体验的关键,但还有一些是良性或者难以发现的,在原型设计中可能会被忽视。原型设计不应该面面俱到,而应专注于关键时刻以聚焦用户的感知。

当原型设计作为探索设计启示和未来想象的一种探索手段时,设计师应使用快速、易于理解的方法来减轻原型设计媒介带来的客观负担和复杂或不明确的思辨主旨所带来的主观负担。